Make a submission here

Blog

María Félix’s High End Jewellery

A previous post considered how María Félix is seen as an inspiration or muse for artists and creators. In my book about her I aim to challenge this idea as one that is a tired cliché frequently used about and against women in such as way that it has robbed them of creative agency in…

María Félix as Inspiration

One of the chapters in my book on María Félix considers the works about her or inspired by her. These are many and varied. Some were commissioned by Félix and some were inspired by her. Of the latter, not all were positive. Félix moved amongst the lively and prodigious artistic and creative circles of Twentieth…

María Félix – Makeup Tutorials

This is an aggregate post collecting transformations into María Félix using makeup and props. “Vintage Icons | Maria Felix Transformation Makeup Tutorial” Vintage fashion and makeup vlogger, Vicky Bermudez, has a seven minute tutorial with keen insights into Félix’s brow and eye make-up. Her introduction to Félix is brilliant. I particularly liked her insightful assessment,…

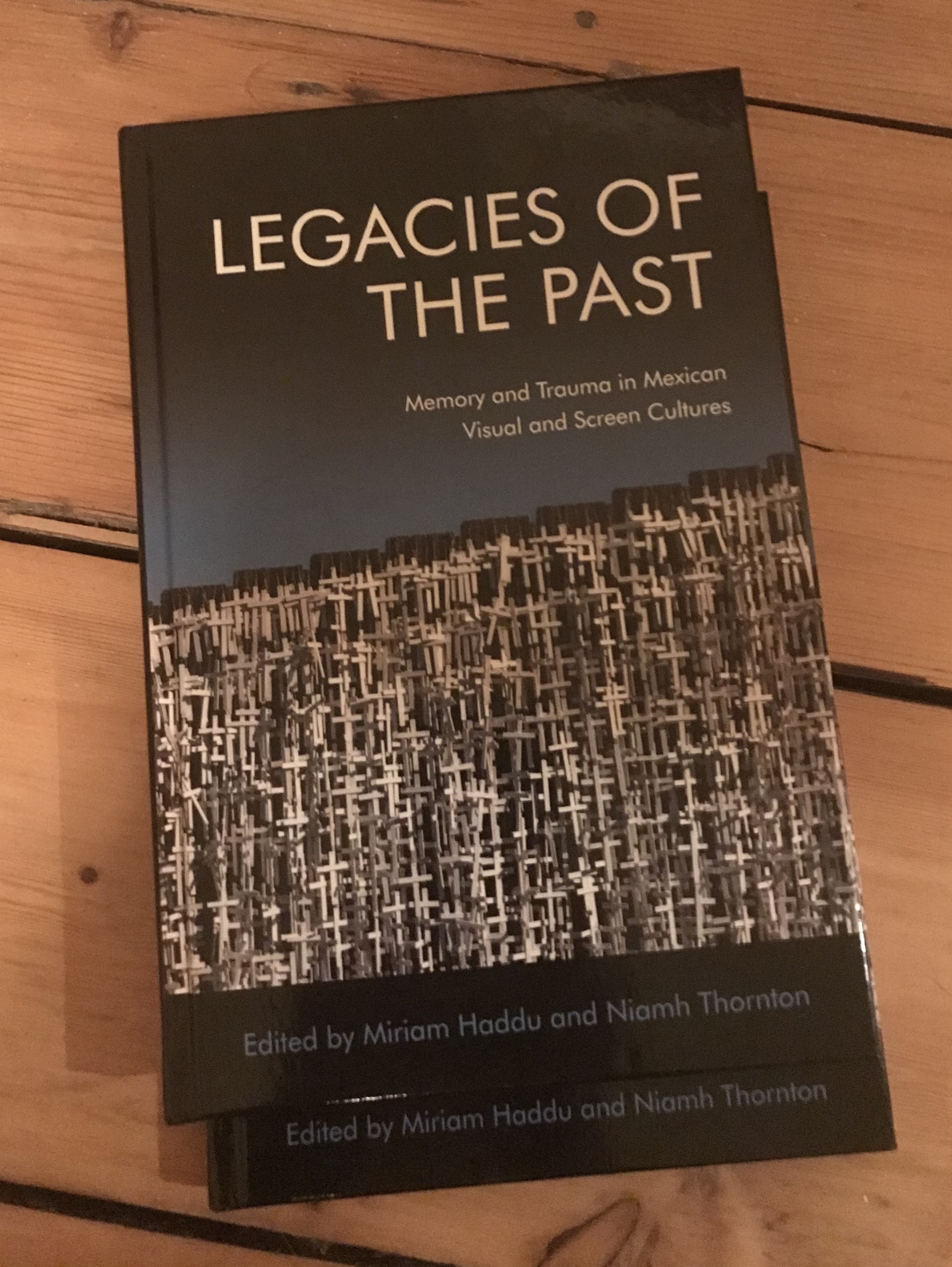

Traces of the Aftermath: Uses of the Perpetrator Archive in Mexican Film

How do we assess found footage that is employed as commentary when it is sometimes ambiguously that of the perpetrator?

Versions and Re-versioning

I have preparing some extra material for students as they study from home. In the past, I have started some classes with a song and link it to that day’s topic. In the absence of this I have compiled some of the songs and in my earnestness to add value and being some pedagogy into…

Reviewing the Muse

Or, what happens when you read multiple biographies at once I often read multiple books at the same time. Whilst researching my forthcoming book on María Félix I have been reading two biographical studies concurrently. The first is a biography of one of Félix’s husbands, Agustín Lara and another is to gain some insight into…

Versions of María Bonita

María Félix had a long term relationship with the bolero songwriter and musician Agustín Lara. They married in 1945 and went on their honeymoon to Acapulco. As legend has it, amongst the many songs he was inspired to write “María Bonita” on their honeymoon. They divorced in 1947. Despite this, the song was frequently sung…

When you find that film…

Previously, I have written about the happenstance of research and, today, I had another. I am writing a monograph about María Félix and found an article in my big Félix file by the actor Diana Bracho. She is critical of Félix and finds her to be representative of a type of character that she is…

How reviews have changed…

I came across these two different takes on the same film.

El monje blanco (1946)

El monje blanco is a film for the completist.