I have just finished writing a chapter on streaming Latin American film in Ireland and the UK. This has involved reading right up to the last minute on how data and algorithms are used to determine what is shown and trying to keep up with controversies, such as the one that blew up in January about the possibility that Netflix will pursue subscribers who use unblockers or proxies. I kept my search to the bigger providers in the market: Netflix, that has considerable cross-market appeal, and MUBI and Curzon Home Cinema, because they appeal to the art house viewer, which is the usual means of distribution for non-Hollywood cinema. I focused my attention on Mexico, a country with a long and highly productive output, and Cuba, which has a more variably output and hasn’t had the same access to international film markets.

I originally looked at MUBI in 2012 and compared their offering to early 2016. The other two were not established as streaming services in 2012, so I only looked at their 2016 offering. The more in-depth discussion happens in the chapter, but what I want to share, here, are the screen shots for 2012 and 2016 for those of you who want a quick insight into the patterns and trends, and who may like it to supplement the chapter when it is published.

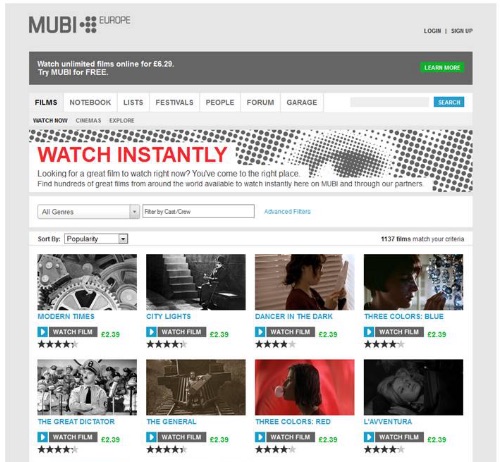

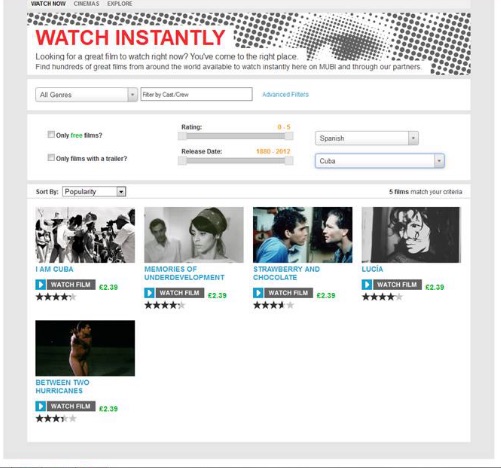

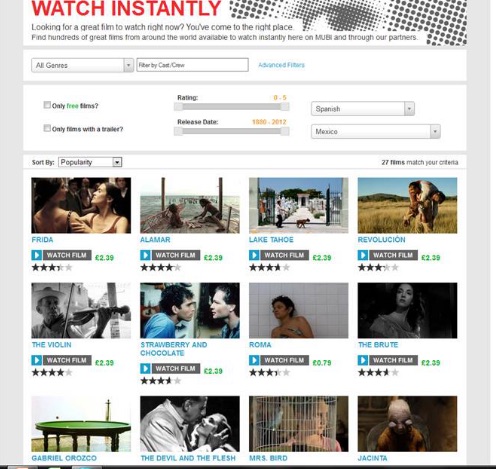

In 2012, MUBI followed a pay-per-view model. According to the founder, Efe Çakarel he set up the service when on a visit to Japan he wanted to watch In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar-wai, 2000). Finding it unavailable he realised there was a market gap for curated arthouse cinema. Here was how it looked in March/April 2012.

Cuba

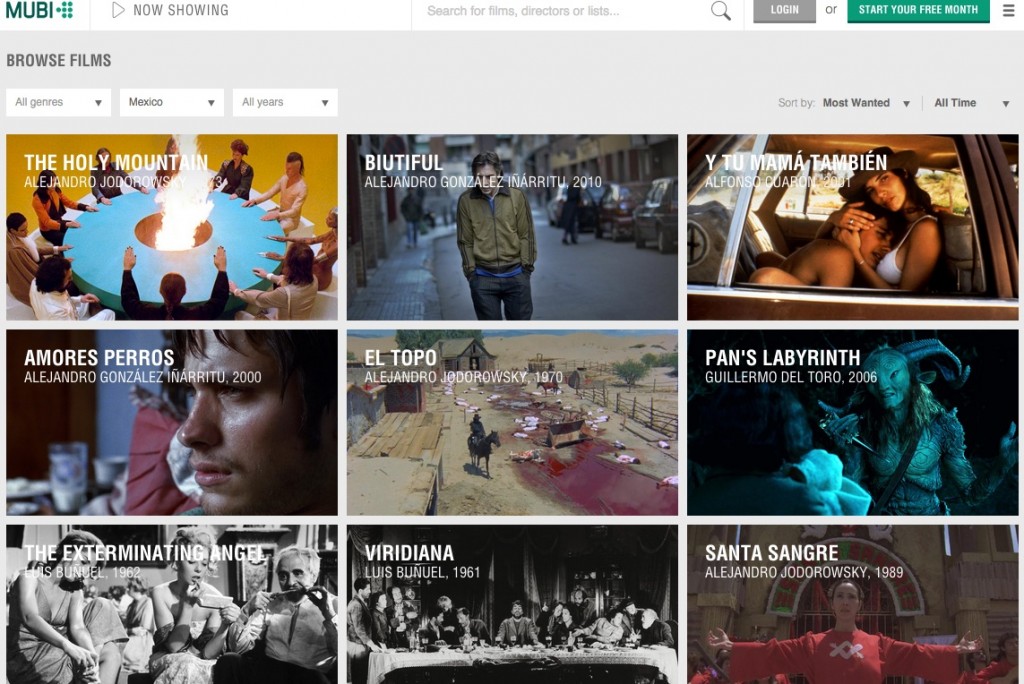

Mexico

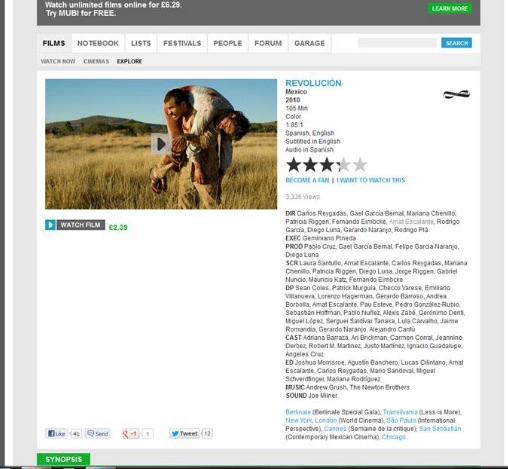

As you can see, there is a variety of films that can be viewed instantly and indefinitely. I highlight the film, Revolución, because it was released on MUBI in an unusual streaming first release.

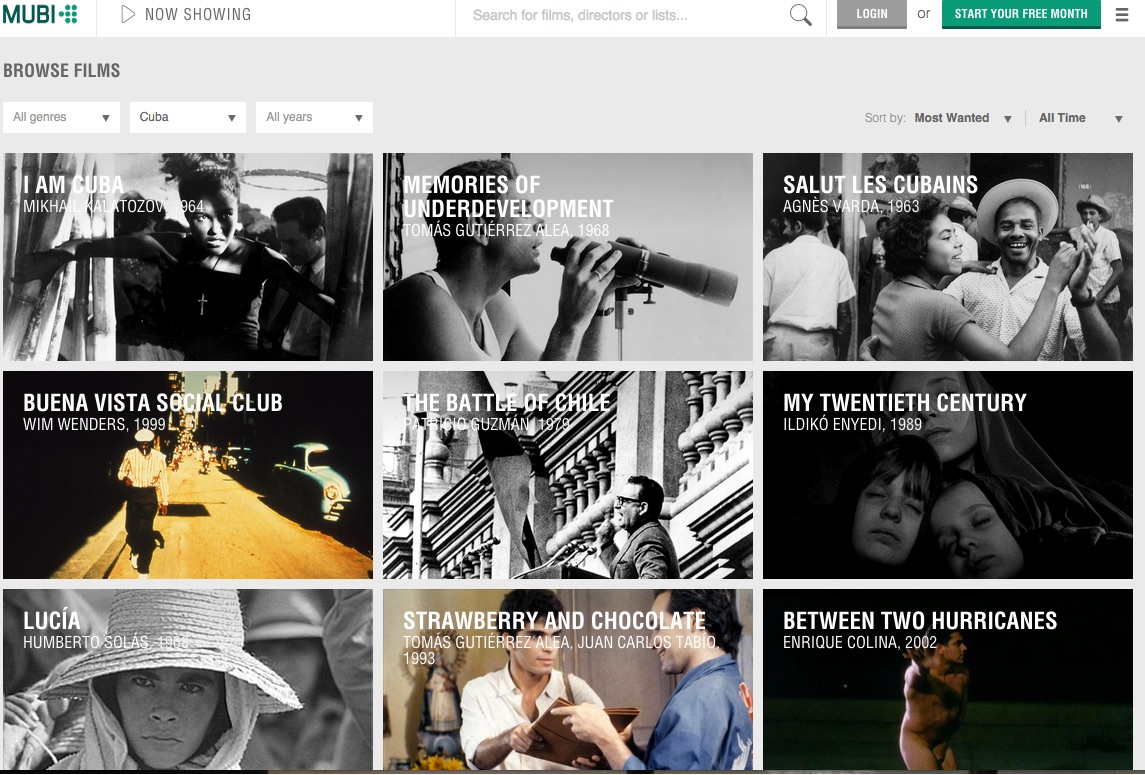

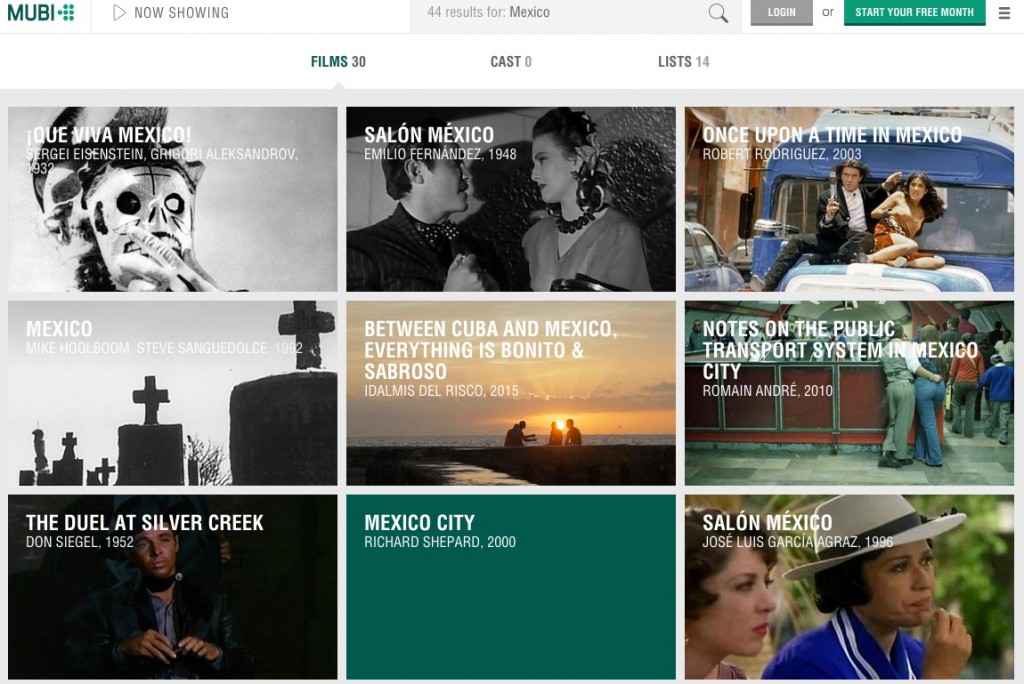

MUBI has subsequently changed its streaming model and now only releases 30 films a day as a carefully curated cinema club. This loses the unlimited on demand access to films. It is possible to see what has been shown previously according to country searches and through film lists curated by subscribers. This is what it looks like in 2016:

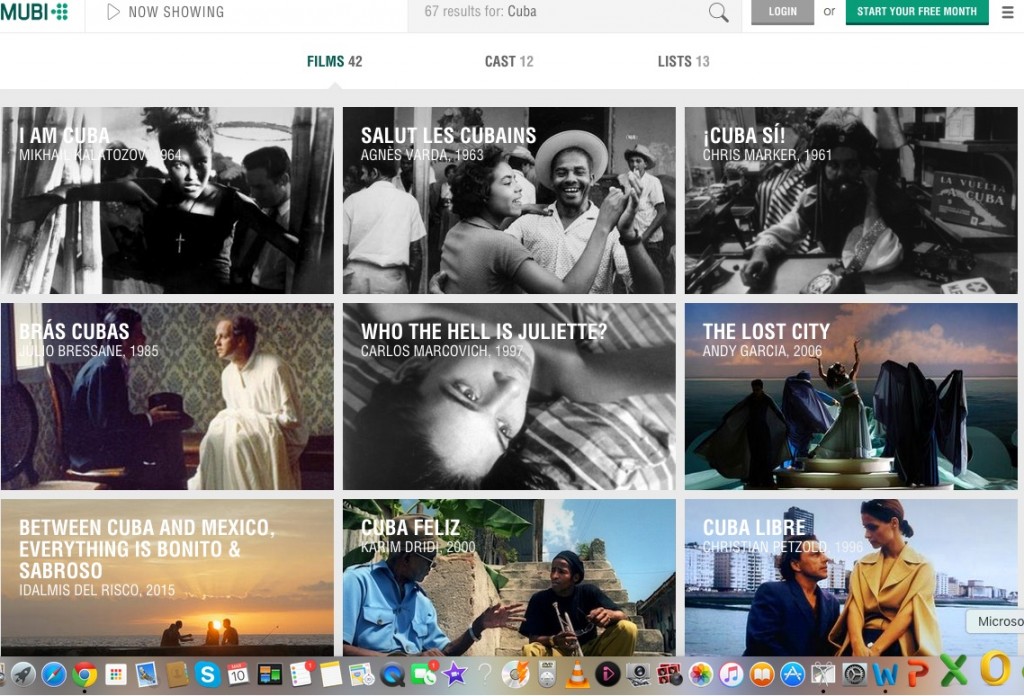

Cuba

Mexico

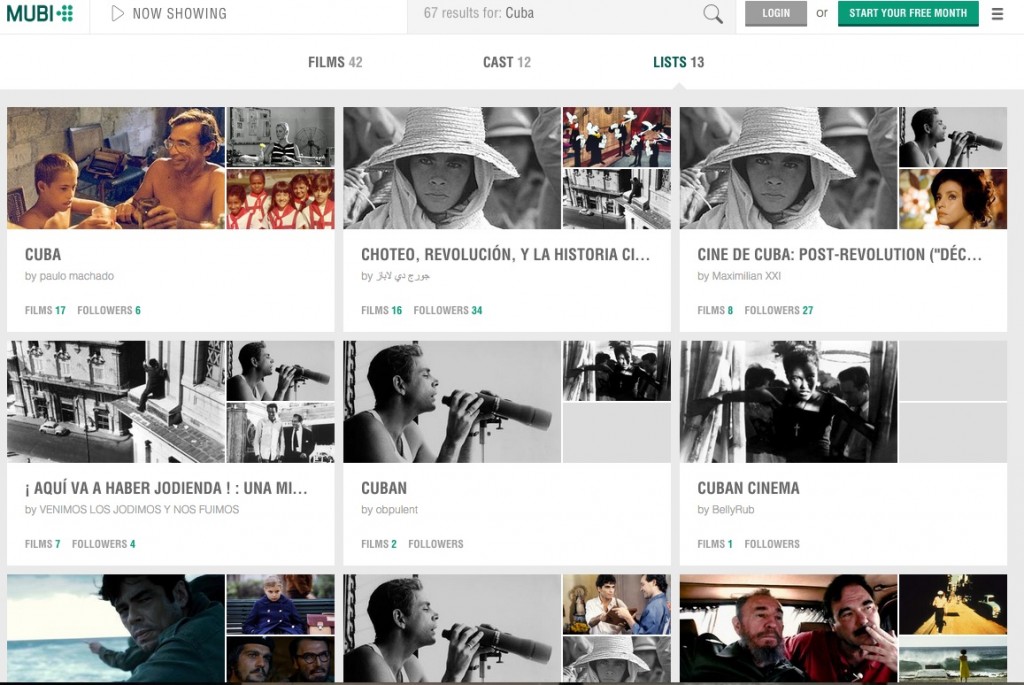

By lists Cuba

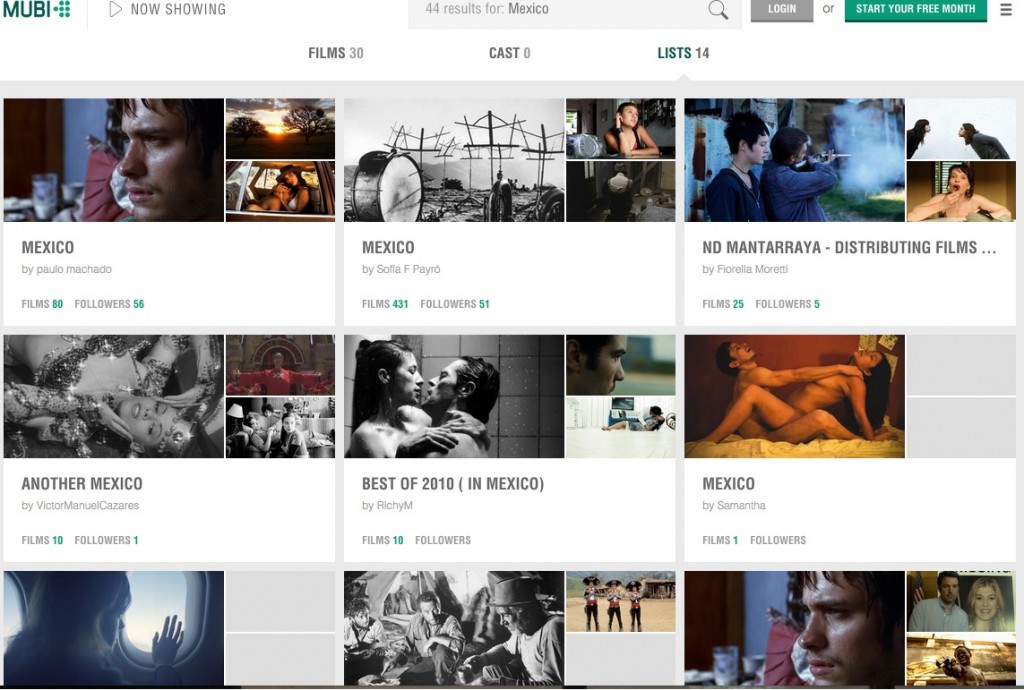

By lists Mexico

Interestingly, if you search for ‘Mexico’ or ‘Cuba’, these mostly show films with these country names in the title,

‘Cuba’

‘Mexico’

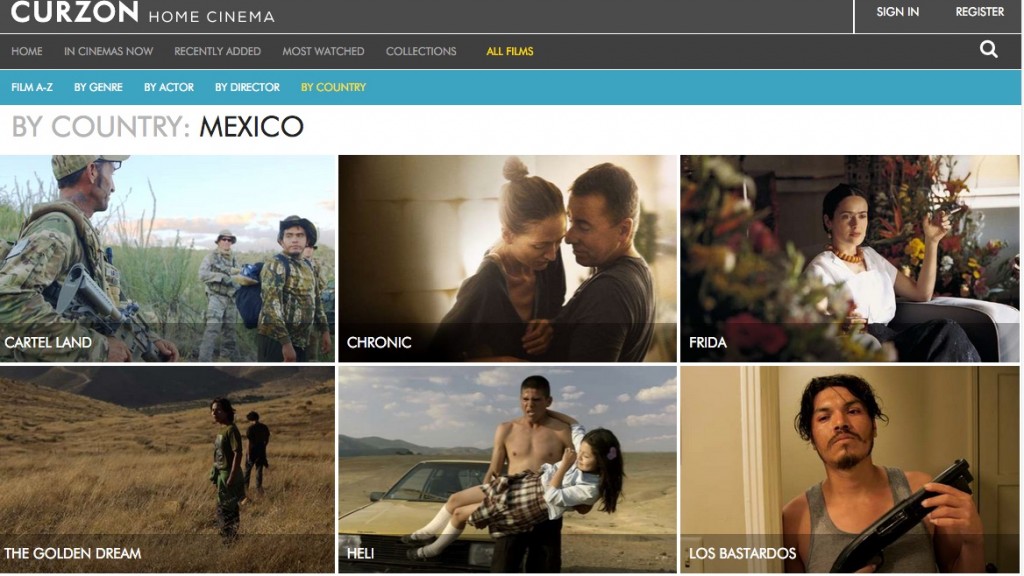

Curzon Home Cinema is attached to the Curzon Cinemas and is an extension of the cinema chain’s offerings to online audiences. It shows recent releases and some older films on demand. The Latin American film offering is dependant on high demand films for which Curzon and its affiliate Artificial Eye has distribution rights in the UK and Ireland. Look for Cuba and there is a thumbnail with an image of Buena Vista Social Club (1999) by the German filmmaker Wim Wenders, but no films are available to view when you click on the image.

The Mexico offering is wider, but nothing near the 100+ films made in 2015 alone.

As you can see some of these are made by Mexicans, are about Mexico or, have a Mexican focus. Therefore, they do propose a challenge to what we understand to mean Mexican or ‘Mexican’ cinema. Elsewhere, Rob Stone (2015, 424) has written about the need to put inverted commas around ‘Spanish’ cinema to complicate how the national category is to be understood. The above examples suggest that a similar strategy should be used for ‘Cuban’ and ‘Mexican’ films. This is central to the discussion in my chapter.

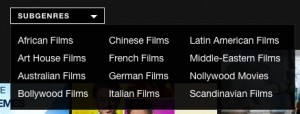

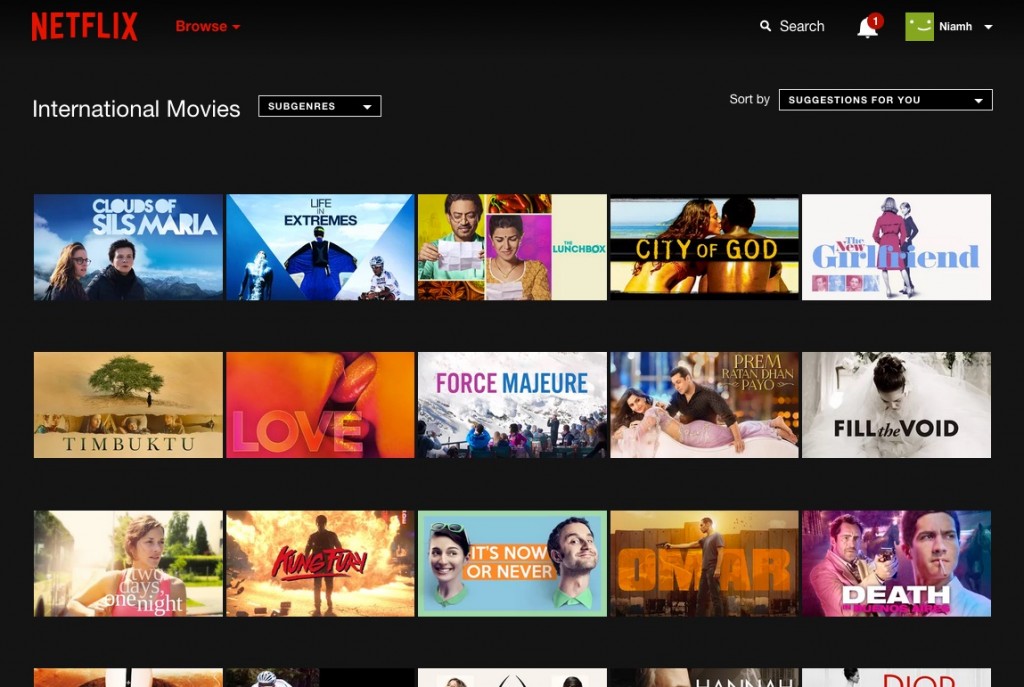

Netflix does not purport to offer arthouse cinema in the way that it is understood by Curzon or MUBI. It has a wide offering – to the extent that it has been accused of being bloated.

On my computer – some TV apps have a different interface – I looked for Mexican and Cuban films by going to the ‘International Movies’ in the ‘Browse’ area, then to the ‘Latin American Films’ under ‘Sub-genres’. The shift between movies and films is interesting so too is the erroneous labelling of films of any region as a sub-genre.

In the Irish and UK site there are only 18 ‘Latin American films’, of which only 4 are Mexican and none are Cuban. The 4 Mexican films are: Days of Grace (Everardo Valerio Grout, 2011), a fiction film about three violent kidnappings during pivotal football World Cup games; a story of a beauty pageant winner caught up in drug violence, Miss Bala (Gerardo Naranjo, 2011); a horror, Here Comes the Devil (Adrián García Bogliano, 2012); and Instructions Not Included (Eugenio Derbez, 2013), a comedy that had the biggest box office earnings in Mexico to date and is currently the highest grossing foreign language film in the US (Cervantes 2016). Miss Bala is the only one of these that got festival and art house distribution, and has received academic attention. The others have gotten little distribution or academic attention, as with many genre films from Mexico. This has much to do with the hierarchical nature of knowledge consumption and the tendency by academics to write about films that appear on curricula, few of which are conventional nor high grossing genre films.

Search for ‘Mexico’ in the search field and this is what appears:

Only Instructions Not Included overlaps with the previous category. Search for ‘Cuba’ and this curious selection turns up:

Some are Cuba Gooding Jr films and the others have tenuous links to Cuba. A change to the dates of my research is the addition of Whatever Happened, Miss Simone? that typifies the transience of research online and the ways content can change within hours or days.

There are two broad conclusions from this search and review: firstly, researchers cannot rely on these streaming services to provide on-demand material, and, secondly, the categorisation and curation can provide an opportunity to re-think how us scholars label Latin American and, more specifically, Cuban and Mexican (or ‘Cuban’ and ‘Mexican’) film. What these streaming services provide could be a new way into thinking about national and transnational film.

Reference

Stone, Rob (2015) “The Disintegration of Spanish Cinema”, Bulletin of Spanish Studies, 92:3, pp423-438.

Follow the hyperlinks for online references.