I have been wearing pink for a week. Often considered a weak colour, condemned as symbolic of the rigid gender binaries being fomented by the marketplace to sell consumer goods to young girls, when thinking about Juárez it means something else. It was first used as a warning sign for women that certain areas were  dangerous. Pink was painted on telegraph poles with a black cross over it. Later, this symbol became a pink cross which was used by campaigners at protests demanding justice, marking (sometimes mass) graves also known as body dumps, and at sites of memorials. Therefore, when the organisers asked those attending the opening to wear pink, it had a very particular resonance. I decided to wear pink in the week leading up to the event. I continued to wear pink for a few days afterwards, to keep the women and the event in mind. My conscious wearing of pink stops today. But, it has been instructive for me to think about what it means to be reminded of these women persistently and in a type of talismanic way through the colour of my clothing. I don’t need to wear pink to think of them. They do come to mind a lot, but not on a daily basis. It is a gesture, one that bears little (probably no) weight for anyone there, and one that requires no hardship on my part. To carry someone (or a group of people) in mind has a type of religious resonance that can have the power to make you reflect, think, and act in whatever ways are possible. It draws on this, but is not motivated by religion in any way. It was also a way of reflecting on my paper in a personal, tactile and visible (to me) way that has helped me to work through what it means to talk about surfaces and the body when both things matter in this context and neither are the most important part of what happens to these women.

dangerous. Pink was painted on telegraph poles with a black cross over it. Later, this symbol became a pink cross which was used by campaigners at protests demanding justice, marking (sometimes mass) graves also known as body dumps, and at sites of memorials. Therefore, when the organisers asked those attending the opening to wear pink, it had a very particular resonance. I decided to wear pink in the week leading up to the event. I continued to wear pink for a few days afterwards, to keep the women and the event in mind. My conscious wearing of pink stops today. But, it has been instructive for me to think about what it means to be reminded of these women persistently and in a type of talismanic way through the colour of my clothing. I don’t need to wear pink to think of them. They do come to mind a lot, but not on a daily basis. It is a gesture, one that bears little (probably no) weight for anyone there, and one that requires no hardship on my part. To carry someone (or a group of people) in mind has a type of religious resonance that can have the power to make you reflect, think, and act in whatever ways are possible. It draws on this, but is not motivated by religion in any way. It was also a way of reflecting on my paper in a personal, tactile and visible (to me) way that has helped me to work through what it means to talk about surfaces and the body when both things matter in this context and neither are the most important part of what happens to these women.

Since the 1990s Juárez has been a very dangerous place to be a woman. There have been thousands raped, tortured and murdered and few have been convicted of these terrible crimes. From 2006 up to very recently, Juárez has been caught up in narco-related violence. I have previously blogged about both of these and the terrible consequences they have had on many lives.

Exhibition at the VG&M

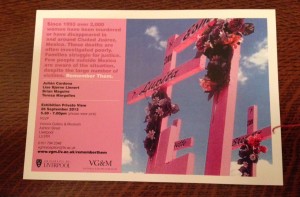

Organised by Chris Harris of the University of Liverpool, the exhibition Remember Them opened on the 26th of September and the symposium took place on the 27th. Both were held at the Victoria Gallery and Museum, at the University of Liverpool. The exhibition continues until the 1st of February 2014.

I would heartily recommend attending the exhibition. It includes the works of four artists: Julián Cardona (Mexico), Brian Maguire (Ireland), Lise Bjørne Linnert (Norway), and Teresa Margolles (Mexico). It merits separate attention. I’ll just mention the work in brief.

Cardona’s work is in the style of press photography. That is his profession. The black and white images have both the immediacy of the press shot and the stylised framing and composition of an artist. They are slightly abstracted from the message of pure reportage and evoke an emotional response through capturing the tragedy of the families’ loss. Family photographs recur in many of the images and are held by subjects either as part of a campaign or to show the absent loved one. There is considerable power and emotion in these.

Maguire’s subjects are women and girls who were killed. His paintings recreate family photographs using his characteristic broad brushstrokes. The paintings are both evocative and flat. There is the absent girl or woman who is known to the artist only through the photograph and the family’s (mostly mother’s) stories. This absent presence is an intangible thing that reminds me of where I stand in relation to these women and girls. They are knowable and unknown. The account of abuse and violent death accompanying the paintings provide individual horrific detail that has become the most salient thing about them, ignoring the particularity of their lives. The paintings bring you somewhere closer through the textured slightly abstracted and colourful recreation of a beloved portrait or snapshot.

family photographs using his characteristic broad brushstrokes. The paintings are both evocative and flat. There is the absent girl or woman who is known to the artist only through the photograph and the family’s (mostly mother’s) stories. This absent presence is an intangible thing that reminds me of where I stand in relation to these women and girls. They are knowable and unknown. The account of abuse and violent death accompanying the paintings provide individual horrific detail that has become the most salient thing about them, ignoring the particularity of their lives. The paintings bring you somewhere closer through the textured slightly abstracted and colourful recreation of a beloved portrait or snapshot.

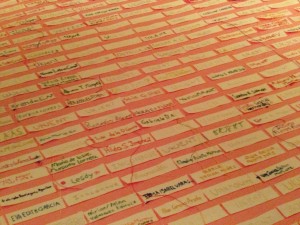

Bjørne Linnert’s work uses embroidered nametags to personalise the women and girl’s deaths through getting participants to sew their names alongside the word “unknown” in all of the languages of the places the artwork has toured. Clothing and these nametags are often the only way of recognising long abandoned bodies. But also, the act of sewing the tags, which she gets people at the places where the work is exhibited to do, is a meditative process and a way to connect the public to the victims. The piece is exhibited in Morse code. Those familiar with

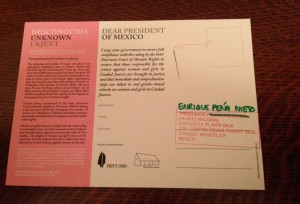

Bjørne Linnert’s work uses embroidered nametags to personalise the women and girl’s deaths through getting participants to sew their names alongside the word “unknown” in all of the languages of the places the artwork has toured. Clothing and these nametags are often the only way of recognising long abandoned bodies. But also, the act of sewing the tags, which she gets people at the places where the work is exhibited to do, is a meditative process and a way to connect the public to the victims. The piece is exhibited in Morse code. Those familiar with  Morse can read lines from the Mexican anthem and US anthem alternated to indicate the implication of the governments from both of these nation states in the fates of the women. Her installation is accompanied by a postcard campaign. Note that the former president’s name has been struck out and replaced with a new one. This isn’t careless or money saving, but a reflection of the depressing lack of action.

Morse can read lines from the Mexican anthem and US anthem alternated to indicate the implication of the governments from both of these nation states in the fates of the women. Her installation is accompanied by a postcard campaign. Note that the former president’s name has been struck out and replaced with a new one. This isn’t careless or money saving, but a reflection of the depressing lack of action.

Margolles video piece is shot from the point of view of someone following behind a water truck, those that clean the highway. She has laid cloth down on ground where victims were found and then rinsed these in water which is then spread on a road in Presidio, Texas. Again, she is demanding that the US take responsibility for its part in the deaths. Through onscreen text, the video clearly places this blame on US drug consumption and illegal sales of arms to Mexican gangs by individuals from the US. The slow pace of the film is meditative. The cleanliness of the road, the clean trucks and cars that pass contrast with the water truck lightly smeared with dust from the water it is spraying.

E. Allison Peers Symposium: Artistic and Academic responses to Femicide in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico

The symposium was divided into two parts. Before lunch there was a viewing of Blood Rising (Mark McLaughlin, 2013), a film made accompanying Maguire on his work as he spoke to mothers and worked on the paintings in Juárez. This was followed by a Q&A with the director. Maguire also actively participated in the discussion reminding the audience that Juárez may seem many things (dangerous, threatening, sensational), but it is also people’s homes, and confessed to feeling “ineffectual” unable to do anything with his “pictures”. McLaughlin and Maguire discussed the limitations on filming because it has been banned in Juárez, their desire to be respectful towards the families, and their awareness that they didn’t want to create another film that simply sensationalised the story. There was a lively discussion about the value of making a film that could be accused of merely telling a story of some terrible distant land that didn’t impel people to campaign or change. This was defended through their assertion that the film is merely one part of a multi-layered campaign (including the paintings, discussions at the EU parliament, cooperation with NGOs, and talks) that they hope will lead to change.

Bjørne Linnert then spoke. She started by asserting her belief that the artist’s role is different from that of a politician and activist, although all can effect change. She quoted a speech by Eleanor Roosevelt to the UN Committee on Human Rights in 1948, who asked, “Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home – so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world,” and it was, in part, from this that she drew her inspiration. She described her process and stated that the project will not end until the situation changes. She currently has 6,700 nametags made by members of the public from around the world. There are 3,100 exhibited in Liverpool some of which were made by local school children. She also described the performance she gave at the opening night, called “Presence”, where she uses her voice to make a loud, declaiming sound that is somewhere between a song and a shout. Each is different in length and pitch, and is followed by a brief pause, again of distinct duration. For her the silence is as important as the voice. Her aim in this is “to connect to the strength and vulnerability in all of us”. It undoubtedly conveyed powerful emotion with the indeterminacy an absence of words can create.

Maguire provided a subjective, non-linear, and both moving and entertaining meander through his creative process. It was practical, personal, and fluid in nature. He started with a list of books which inspired him to create this work, most significantly Daughters of Juarez and mentioned a quotation from the Irish socialist thinker James Connolly that rings true for him that “The worker is the slave of capitalist society, the female worker is the slave of that slave”. He connected his prior experiences in Ireland with what he heard about and witnessed in Mexico. He compared this with his work in prisons in both Dublin and the Long Kesh in Northern Ireland, and drew on his knowledge of people and places in power and criminality in both countries. He clearly stated that what has been happening in Juárez can and is happening elsewhere. His talk echoed that of others earlier and later in the afternoon, that we cannot countenance an us and them we must think of solidarity with others. He also spoke of the practicalities of moving in a space like Juárez where both he and McLaughlin were conspicuous as well as the respect he has for the women he met who campaign for justice for their dead children.

After lunch the academic programme began. Nuala Finnegan, University College Cork, provided a clear overview of the current state of play in Juárez and the multiple debates surrounding important details such as, start dates, numbers dead, reports issued, laws passed and the subsequent inaction, as well as the terminology employed (some use femicide, others feminicide). As she discussed, there has been a proliferation of theories which have led many authors and filmmakers to approach the events with whodunit style narratives. She considered how the victims were painted as sluts in the past and how Juárez has become a feminised space of violent death with a subsequent Juarezisation of Mexico abroad. In other words, the perception that this violence becomes the dominant narrative. Drawing on anthropologist Rita Laura Segato’s consideration of Juarez; Emmanuel Levinas theorisation of the value and meaning we give to the human face; Judith Butler’s response and expansion of his work; a consideration of how “suggestive relationships” and “empathic encounters” can be created; and reflections on how there can be a valorisation of worthy victims and immediacy in much of the artistic production. Focused on artistic creation she too wondered at how we can make the “elsewhere of the world” closer to the viewer, to the here.

Julia Banwell, University of Sheffield, considered the “filthy physicality” of Margolles’ work. Providing examples of Margolles’ installations at several events that reference Juárez, she considered Margolles’ use of pollution and contamination. Margolles often uses traces left behind by bodies, such as the dirt from the body dumps washed through water carried by the truck in the film in the exhibit. At times her use of bodily matter is more visceral. For Banwell, the absence of the bodies in the way that Margolles deploys these traces forces the viewer to look. Margolles’ art always provokes controversy and much of the discussion afterwards was about consent and the ethics of producing work using remains of those who have been brutally and violently killed. Banwell was careful to emphasise that the families consent to its use. I always find Margolles work to be deeply disturbing and sometimes, for me (although not the work in this exhibit), it can cross the line into a kind of bad taste and a violation of bodily integrity that I cannot reconcile myself with.

Sarah Bowskill, Queen’s University Belfast, spoke about fiction and femicide/feminicide in English, If I Die in Juarez, The Vampires of Ciudad Juárez, Desert Blood, and The Dead Women of Juarez, as well as 2666, which, although written in Spanish by a Chilean, has had considerable reach in its English translation. Many of these are of the type that use the whodunit format referred to by Finnegan, drawing on the generic tropes of detective fiction to variable success. She provided examples of a type of pattern that is apparent in the paratextual elements of the novels, that is, those parts that are not integral to the narrative proper (blurbs, forewards, afterwards, etc). These attest to the facts of what is taking place and express a wish for change. She navigated the differing tone, style and characteristics of the novels, and assessed how successful they were in constructing a convincing and empathetic account of Juárez and of “the poor brown women” (in Alicia Gaspar de Alba’s words) who live and are killed there.

My paper came at the end. I spoke about two films which were released in 2006: Bordertown (Gregory Nava) and The Virgin of Juarez (Kevin James Dobson). Again, both involve whodunit narratives and follow US-based journalist protagonists who cross the US-Mexican border to write stories about the murdered women of Juárez. Renowned female performers play the protagonists of the films, Jennifer López and Minnie Driver, respectively. My paper was concerned with what their star bodies mean, with all the glamour and obsession with surfaces that can imply. Particularly, I consider the significance of their racial subjectivity and how it is integral to the plots of the films: López who is read as Latina (read curvaceous, sensual, and passionate) and Driver as white (therefore, she is to be understood as contained, and controlled). I traced how López’s character reflected this conceptualisation eventually leaving behind her learned whiteness and returning to her authentic Latina self, whilst Driver in this particular conceptualisation of race, as a white woman could only ever be an outsider. I drew from Richard Dyer’s White in my discussion, but also work by those who have discussed the Latina body (here, I must emphasise that there is no such thing as a singular Latina/white/black/etc body, but just ways that such bodies are “constructed and mediated through discourse” [Mendible, 5]), for example, Myra Mendible, Suzanne Chávez-Silverman, amongst others. My concern with this work can be that it deals with the superficial, something that is far removed from the immediacy of the horror of torture and death. However, these women are killed precisely for how their bodies are controlled and dominated, they are adjudicated as valueless, objects to be traded, lacking in power, mere things to be toyed with, and discarded in dumps. To consider what these bodies mean on screen and to consider the power and value ascribed to women’s bodies is to reflect on what it means to be human and a woman there and here. It is a subject I will reflect on further in the future.

This all brings me back to why I wore pink. It is pure surface, a pigment with particular light-reflective qualities. Despite that it had significant meaning for me last week. It is also a colour that resonates for the campaigners. For some, art is just surface, even when it entails spreading water across a space that may penetrate surfaces. I think the exhibition, and the artists’ and academics’ discussions showed that these surfaces have considerable power and weight. They may not effect immediate change. They will hopefully shine a light on what is happening and challenge us to think beyond a them and us and realise that to remember them is to remember the us who are looking, buying the goods they make, and participating in a system that divides them from us.