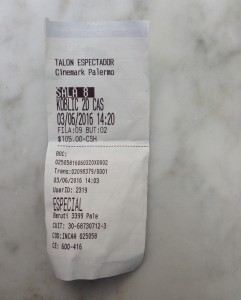

I am currently on a trip to Buenos Aires as part of a project on commemorative practices. My work will focus on Mexico, but Argentina is a locus for much of the critical work around this in Latin America and I wanted to see some of the physical spaces first hand. Whilst here, I got to see a new release starring Ricardo Darín, Kóblic (Sebastián Borensztein, 2016). Here is a link to the trailer.

Set in 1977, the story is about a former captain, Kóblic, a pilot with the Argentine navy. He is charged with piloting the so called “vuelos de muerte” [death flights] during the Proceso de Reorganización Nacional/Dirty War (1976-83). Individuals who had been held and tortured in the detention centres were thrown from these planes into the sea to die. Traumatised by having to carry out these flights, Kóblic finds himself unable to obey orders and goes on the run in Argentina. The narrative unfolds as a thriller with a wish fulfilment revenge plot, Western motifs, and a romantic dalliance thrown in. For the most part it is a pacy and watchable film, and yet, I left with considerable reservations that I have spent some time mulling over. These have to do with plotting, wardrobe, character development, and my own viewing experience.

Plot and Wardrobe

There are rather odd plot and wardrobe choices, not least Kóblic’s decision to stay in Argentina. He also keeps his military ID in his wallet and continues to wear his aviator glasses. The former allows for an all-too-neat plot reveal, while the latter is more than a superficial period wardrobe choice and does not read as true. The glasses have associations with the armed forces – think Tom Cruise in Top Gun (1986) for a romanticised version of US Cold War military representation. This makes them key identifiers, a fact that is reinforced by another member of the force in pursuit of Kóblic, who also wears them. A longer piece could be written on the recurrence of these glasses and their US associations in Latin American films of this era. Their presence is highly resonant and seem like an attempt to complicate his character that felt clumsy. Like his decision to stay and to keep his ID, I was distracted by his need to hold on to something that would so clearly reveal his identity.

Death Flights

The Death Flights feature heavily in another film set at this period. Garaje Olimpo (Marco Bechis, 1999) has a powerful opening sequence from the point of view of one of these flights showing an aerial shot of the city of Buenos Aires starting at the water and opening out to a shot of the city. This recurs at later key points in the film. It is only as the plot develops that its full significance is revealed. The point of view of the plane is not made clear. It could be from the pilot, the guards, or one of the detained. Point of view is a powerful tool, and potentially invites us to identify with the deeply troubling position of being one of the individuals who have just committed this act. Garaje Olimpo leaves no doubt that that this is a terrible position to inhabit – whether as perpetrator or victim. The film is primarily focused on the fate of an individual woman who is detained and tortured. Therefore, starting from the position of those implicated in the process is to ask the audience how they are responsible for what took place, to question their own ignorance, or to feel the terror of being a victim. Kóblic is different. The horrors of the dictatorship may be read into the sordid and corrupt ways of the small town in which he is hiding, and may be alluded to in the flashbacks to the death flights, but they are physically distant and allusive. This is part of the reason I came away from it feeling troubled.

Reception

Reading a review in the Hollywood Reporter gets to the nub of another reason I found it troubling. I saw it in a screen with two men who would have been the same age Kóblic is supposed to be in this film and could have been on one side or the other in this narrative, or have known people caught up as perpetrators or victims. We sat in our tiered seating in a modern multiplex in our own rows. The men exchanged some pleasantries beforehand in a slightly nervous fashion about it being like a private screening, but didn’t speak afterwards. They did not seem to know each other. Their presence made me very aware of how the film could be consumed and, like the Hollywood Reporter reviewer, I was conscious that “it’s probably worth reflecting on that such pilots are still there in Argentina, a few years older now, but leading normal, unpunished lives”. Had one of these men at the screening with me been a pilot? The reviewer goes on to say that, because no justice has been served, “The script therefore has to bend over backwards to show that Koblic is a fundamentally decent man, someone we should be caring about”. I’m not sure I agree with that corollary, film can lead to new realisations about the past and can posit that some who carried out terrible actions were wrong to do so, even if justice has not been served. The filmmaker also goes beyond just making Kóblic decent. In fact, he is heroic in the end and that is what really makes this film troubling. There is a considerable responsibility in creating a film from the perpetrator’s perspective. Making him a figure with whom we should empathise, because he found some moral decency and is now haunted by nightmares, is far from tackling perpetrator complicity or guilt. I came away wondering: if one of my fellow audience members was a perpetrator, could he feel redeemed by this film? I suspect he could.

Reading a review in the Hollywood Reporter gets to the nub of another reason I found it troubling. I saw it in a screen with two men who would have been the same age Kóblic is supposed to be in this film and could have been on one side or the other in this narrative, or have known people caught up as perpetrators or victims. We sat in our tiered seating in a modern multiplex in our own rows. The men exchanged some pleasantries beforehand in a slightly nervous fashion about it being like a private screening, but didn’t speak afterwards. They did not seem to know each other. Their presence made me very aware of how the film could be consumed and, like the Hollywood Reporter reviewer, I was conscious that “it’s probably worth reflecting on that such pilots are still there in Argentina, a few years older now, but leading normal, unpunished lives”. Had one of these men at the screening with me been a pilot? The reviewer goes on to say that, because no justice has been served, “The script therefore has to bend over backwards to show that Koblic is a fundamentally decent man, someone we should be caring about”. I’m not sure I agree with that corollary, film can lead to new realisations about the past and can posit that some who carried out terrible actions were wrong to do so, even if justice has not been served. The filmmaker also goes beyond just making Kóblic decent. In fact, he is heroic in the end and that is what really makes this film troubling. There is a considerable responsibility in creating a film from the perpetrator’s perspective. Making him a figure with whom we should empathise, because he found some moral decency and is now haunted by nightmares, is far from tackling perpetrator complicity or guilt. I came away wondering: if one of my fellow audience members was a perpetrator, could he feel redeemed by this film? I suspect he could.

Good Badman

At a screening of the film, the director felt the need to emphasise that he did not wish to make this a sympathetic portrait of a perpetrator: “Kóblic no existe, es un personaje de ficción. Lo que sabemos todos es el contexto histórico, que hubo cientos de vuelos, cada uno debe haber sido un infierno y uno puede imaginar que puede haber pasado de todo” [Kóblic does not exist, he is a fictional character. We all know the historical context in which there were hundreds of flights, each one of them must have been hell and you can only imagine that all sorts must have happened on them]. The flights are portrayed as terrible, but the primary trauma is experienced by the perpetrator, not the victims. Thus the victims’ stories are absent from this narrative other than through other proxy stories of family abuse. In Kóblic, the perpetrator, not the victim, gets to be an avenging hero in the mould of the good badman of the contemporary Western.

Bad Badman

Another point of contention is the badman in the film. Much praise has been heaped on Óscar Martínez’s performance as the corrupt police officer, Velarde (see, for example, this review). He is a cartoon villain. He wears a bad wig – one of his first gestures in the film is to adjust it in a parody of the Western sheriff fixing his hat-, he has false teeth, and is greasily lascivious. All of this Martínez performs well. Playing opposite this character Kóblic can shine. Velarde provides space for Darin to look thoughtful and reflective. Kóblic is a man haunted by his past and the plot is built around him being bothered by such bad badmen as Velarde. It reduces the potential for nuance and sidesteps the possibility for real depth in favor of a slash and burn revenge narrative. In the absence of actual justice, the cartoonish badman (and his sidekicks) provide an opportunity to enact fantasy justice.

Conclusion

Kóblic should get international distribution because of Darín’s star power and the European and US producers and distributors attached, also, the Dirty War has much traction internationally, and it is a well executed film. This is a genre film combined with long takes of beautiful landscape that, in some ways contains much visual pleasure, but it is a worrying venture into exploring perpetrator narrative.