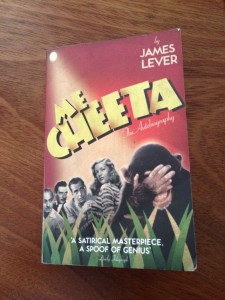

Me Cheeta: The Autobiography James Lever London: Fourth Estate (2008) 2009.

I spoke at the Revisiting Star Studies conference in June held at the University of Newcastle about the online presence of Mexican male stars from the so-called Mexican Golden Age. As part of this I made reference to my article on María Félix and Dolores del Río , because what their fans have generated is in marked contrast to fans of their male contemporaries. Afterwards, a fellow conference goer came up to me and asked whether I had read Me Cheeta saying that in it the eponymous chimpanzee was very vicious towards del Río. Intrigued, I bought it. Del Río is, indeed, one of the victims of his bitchy, sarcastic, funny, and poignant memoir of the Golden Age of studio era Hollywood, the “Dream Factories” (73) and the dreamers who inhabit it. Del Río gets some of his ire, but is more generally cast as a victim of an attack by him that is frequently alluded to but only fully articulated in a final denial at the end of the book. There are others who are also singled out for his derision, Greta Garbo, Mickey Rooney and Charlie Chaplin, whilst some of his contemporaries get much better treatment, especially Johnny Weissmuller who played Tarzan. Cheeta obviously loves him unconditionally. Much of the sympathy for Cheeta is played out through this relationship and his mistreatment within the studio system, because in many ways he is an unpleasant and nasty chimpanzee saved only by this tragic aspect of his experiences and the clever humour of the novel.

To call it a memoir is, of course, to mistaken its genre. It is a novel that draws on many of the conceits of memoir, star autobiography and issue-driven books. It follows Cheeta’s story chronologically with some diversions over and back to the present day and his relationship with his current carer, Don. He is inclined to rant at various moments. These can be consonant with the era/person/topic he is dealing with, there are further moments where he appeals to an addressee who appears to be in his company and there are also apparently random digressions typically to talk about his desires for cigarettes or alcohol.

One of the many digressions refers to a pseudo organization, No Reel Apes, purportedly set up by Don and Dr Jane Goodall to prevent cruelty to animals by banning their use in the entertainment industry. He describes the organisation and, at first, appears to praise Don and Jane’s good work, but clearly disapproves. His scathing critique of their work is typical of the tone of the novel. At first he sets it up as a positive organization: “It’s only that I felt obliged to touch on some of the problems that Don and the attractive Dr Goodall are eager to highlight for their No Reel Apes campaign. Cruelty to apes in the name of entertainment is obscene and must stop” (85). This is by way of an explanation for his references to the darker elements of his capture and transport to the US and his treatment in captivity. So far, it appears very serious and earnest. This tone is soon upended in the remainder of that sentence: “though of course it can lead to some absolutely tremendous movies, and I personally had a wonderful time in Hollywood” (85). This is typical of the constant shifts between tones that both mimics the earnest, self-aggrandising, obsequiousness, false modesty and gossipy insider nature of many star biographies and consistently undermines these. This segment continues with a rant about CGI, which is the (for him lamentable) replacement for real animals on screen: “Does Buzz Lightyear ever suffer for his art? No, and that’s why he’s no good. Though, I do have to say, the children [he visits in hospitals] haven’t the faintest idea who I am. Well, anyhow, CGI, that’s supposedly the way forward, according to Don and Jane. Support their campaign: www.noreelapes.org or something like that” (86). There is a snarkiness to his comments that are also filled with sadness, which underscores the whole book and is what saves it from being nasty and shallow and allows some space for empathy. In this same chapter entitled “Big Break” he talks about his arrival to Los Angeles and his “discovery” as an actor, he describes the “starving and beating [that] all formed part of Louis Mayer’s painstaking grooming process-almost exactly the same process as MGM put Ava Gardner through” (86). Thereby the author combines both an implicit critique of the mistreatment of animals and parallels it with the mistreatment of the stars by the studios, albeit in a jokey aside. Cheeta as narrator is used as a knowing ruse to draw attention to the cruelty of the studio system towards human actors.

One of the many digressions refers to a pseudo organization, No Reel Apes, purportedly set up by Don and Dr Jane Goodall to prevent cruelty to animals by banning their use in the entertainment industry. He describes the organisation and, at first, appears to praise Don and Jane’s good work, but clearly disapproves. His scathing critique of their work is typical of the tone of the novel. At first he sets it up as a positive organization: “It’s only that I felt obliged to touch on some of the problems that Don and the attractive Dr Goodall are eager to highlight for their No Reel Apes campaign. Cruelty to apes in the name of entertainment is obscene and must stop” (85). This is by way of an explanation for his references to the darker elements of his capture and transport to the US and his treatment in captivity. So far, it appears very serious and earnest. This tone is soon upended in the remainder of that sentence: “though of course it can lead to some absolutely tremendous movies, and I personally had a wonderful time in Hollywood” (85). This is typical of the constant shifts between tones that both mimics the earnest, self-aggrandising, obsequiousness, false modesty and gossipy insider nature of many star biographies and consistently undermines these. This segment continues with a rant about CGI, which is the (for him lamentable) replacement for real animals on screen: “Does Buzz Lightyear ever suffer for his art? No, and that’s why he’s no good. Though, I do have to say, the children [he visits in hospitals] haven’t the faintest idea who I am. Well, anyhow, CGI, that’s supposedly the way forward, according to Don and Jane. Support their campaign: www.noreelapes.org or something like that” (86). There is a snarkiness to his comments that are also filled with sadness, which underscores the whole book and is what saves it from being nasty and shallow and allows some space for empathy. In this same chapter entitled “Big Break” he talks about his arrival to Los Angeles and his “discovery” as an actor, he describes the “starving and beating [that] all formed part of Louis Mayer’s painstaking grooming process-almost exactly the same process as MGM put Ava Gardner through” (86). Thereby the author combines both an implicit critique of the mistreatment of animals and parallels it with the mistreatment of the stars by the studios, albeit in a jokey aside. Cheeta as narrator is used as a knowing ruse to draw attention to the cruelty of the studio system towards human actors.

As well as being a delightful and entertaining read, Me Cheeta also provides some interesting insights into the studio system, its heyday and its demise, albeit veiled in sarcasm and in an un-academic style. It is largely accurate, but has taken licence with the truth. It is a novel after all.

To focus on the Mexican interest, aside from the frequent references to alleged behaviour with del Río, stories of her first husband’s production roles, and mentions of Mexican actors, such as Lupe Vélez, Weissmuller’s third wife, he also recounts details about the Mexican production, Tarzan and the Mermaids (1948). It was a shambolic shoot which he describes as having two big problems: “The first was that there wasn’t a script, the second was that nobody could quite make up their mind whether they were vacationing or not” (251). The six page description of his involvement on the shoot before he was taken away for unprofessional behaviour both sums up how disposable stars are (at this stage of the novel his stardom is convincingly consonant with those of his fellow human actors) and of the malaise that the film industry was suffering at this point. It is to Lever’s credit that despite Cheeta being a largely unlikeable, egotistical and unreliable narrator this moment is deeply poignant and has echoes of the treatment of human actors. Cheeta is dismissed and easily disposed of as is evidenced in the director, Robert Florey’s reported speech after Cheeta’s “lapse”: “‘Uh, Wait. I tell you what we can do to fix this,’ Florey said. At last, a bit of thought, a bit of direction. ‘We can get Sol to airfreight another one down this evening, right? Tell him to talk to – what’s his name? Gately. Get another one out here by tomorrow morning, and we’ll call this morning a wipe. Light’s not right anyway” (256). The aside, “At last, a bit of thought, a bit of direction”, provides commentary, keeps the mood light and reminds the reader of Cheeta as victim of their glib decisions. Mexico, and more specifically Acapulco, figures as a playground for the stars whose light is dimming and whose partying, like that of Cheeta, is impeding their performances. His easy replacement is tragic, but also indicative of a system unravelling.

Me Cheeta may not be entirely accurate in all of its details, but it does conjure up a period and impels the reader to think about the mistreatment of animals in Hollywood during the studio era. Given Cheeta’s convincingly human voice and agency, combined with his stories of those human stars around him, it prompts us to think about the brutality of the system and its tragic consequences. It is a strength of the novel that it wraps the tragedy and poignancy of this era into a highly amusing and witty yarn.