Breaking Bad is a high quality drama created by Vince Gilligan which follows the story of Walt (Bryan Cranston) who, when diagnosed with lung cancer, decides to become a methamphetamine cook. This decision is justified through the lack of affordability of medical care in the US, a highly politicized topic there. As a chemistry teacher and car wash worker with a stay-at-home pregnant wife (Anna Gunn) and a son (RJ Mitte) with Cerebral Palsy, neither his health insurance nor his income can cover decent medical care. As well as paying for healthcare, he also expresses a desire to amass sufficient money to leave his family financially secure. The plotting is careful and his turn to violent and dangerous criminality is not instant, but a gradual process shown as a series of responses to developing situations as well as an emerging psychological process. The narrative arc reveals itself over the course of the 5 series with cleverly placed hints throughout of the character’s development. It is quite brilliant in its exploration of the how and why that the gerund “breaking” suggests. That is, Breaking Bad explores what makes a person turn and how they can go from being a calm, contained, and brow beaten individual to performing brutal acts of criminality over time. It is an impressive series, and one that deserves the attention and awards it has gotten.

Place is integral to this series. Shot in New Mexico, it moves the usual border story from the more familiar Texas or Arizona to a lesser populated state similarly effected by the tensions of the US-Mexico border. Landscape is cinematically shot mostly by Michael Slovis and makes full use of the impressive, flat, vast open spaces and beautifully rendered sunsets and sunrises of New Mexico, even dwelling on these to assert their significance as a context for this narrative. As has been written about with regards to John Sayles’ Lone Star (1996), the vertical lines of these shots are a consistent visual reminder of the border between the US and Mexico.

The border looms large in the story as an integral element of the plot and as metaphor. Just as in Lone Star, many lines are blurred between right and wrong, good and bad, whereby moral dilemmas and their resolution are at the core of the plot. Implicitly, the audience is being asked to consider what they would do in his ever-evolving situation. Would you accept the money from your ex-girlfriend who took your business concept and became a millionaire? Do you go in with force in a given situation or resolve it through other methods? Is it right to kill that person? Do you tell your wife what you are up to and, at what point? (I’m being deliberately oblique to avoid spoilers). This is all cleverly rendered.

Unlike Lone Star, the representation of the real border and those who are from the Mexican side is more troubling. As plot elements, there are recurrent Mexican characters, mostly drug dealers, who must be negotiated with, avoided or confronted in order to establish a claim over the local market.

So, what of these Mexican characters? First it’s worth considering the context in which this series is made. It is at a very interesting time for what the border means in the US, politically and culturally. It is a contentious political topic. President Obama’s government, amidst promises of better immigration laws including the introduction of the Dream Act, has deported more illegal immigrants than his predecessors. Laws were brought in by Arizona state legislature to ban the teaching of Chicano and Mexican texts as subversive and dangerous. The Bush administration spent millions reinforcing the border to hamper illegal immigration. At the same time, in the recent elections the Republicans who harnessed a lot of anti-Latino sentiments in their last presidential campaign were forced to confront the fact that they lost the race because they failed to attract the Latino vote. They have become the largest ‘minority’ in the US and are now being actively courted.

On the Mexican side of the border the last few years have been dramatic. As I have previously written, Mexico has experienced serious problems, particularly between 2006-12, because of government policy and violence by drug gangs, the Narcos. This has been most acutely felt along the border, but also in the gulf and central states. Detail on these can be read here. It has suffered acutely from the global downturn and has seen millions of migrants returning (voluntarily or through deportation) from the US because of the economic collapse there. Meanwhile, it has received a large number of migrants from Central America fleeing terrible gang culture (largely associated with the drug trade) in these nations. Conditions are tense on both sides.

The Mexican characters in Breaking Bad are one of the weaknesses of the series. They are often more psychopathic than any of the locally produced ones whether that is the meth addicted dealer Tuco (Raymond Cruz) of season 1; the disturbed, vengeful and largely silent brothers of season 3; or the over-sexed and sleazy Narcos, whose rancho the characters visit in season 5. Even Gus (Giancarlo Esposito), who for many seasons is one of the chief drug distributors, his Chilean (read Latino) roots and his training as a dealer in Mexico render him highly dangerous thus allowing him to dominate the local market.

A useful insight into this channelling of a particular style of bad Mexican is through the use of the actor Danny Trejo as Tortuga. As this song by Plastilina suggests, Trejo is allied with a particular b-movie, hard man character. He is an actor whose extensive roles (243, last count on imdb.com) as a Latino badass in genre movies was channelled by Roberto Rodríguez in the hard man roles with a heart of gold in the Spykids (2001-11) series, From Dusk to Dawn (1996) and Machete (2010). Trejo’s presence signifies more than the sum of the character he is playing. It draws on this complex interplay between ubiquitous roles and the character he performs at that particular moment. In Breaking Bad he carries this history with him and the scriptwriter is not called upon to flesh out his past, he is by implication a sum of previous characters. This then acts as a visual and narrative shorthand whereby Trejo, depending on the inflection, can be the violent, dangerous underdog who upsets the status quo or stands in for all greasy, dangerous, unreliable and slippery Mexicans without being fleshed out more significantly.

*Spoiler alert*

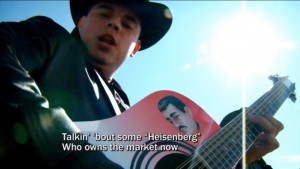

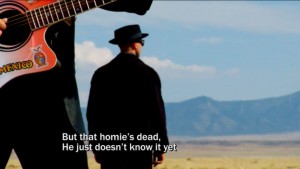

Trejo’s role is worth dwelling on because he is one of the best-known Mexican-American actors in this series and he embodies the disquieting approach taken towards the representation of Mexicans in Breaking Bad. He appears in just two episodes, “Negro y Azul” Season 2 episode 7, where he plays a prominent role, and “IFT” Season 3, episode 3. I’ll focus on “Negro y Azul”. This episode is markedly Hispanic/Mexican in theme and focus. The title translates as black and blue. An eponymous narcocorrido sung by the reknowned

Los cuates de Sinaloa plays before the opening credits and extolls Heisenberg/Walt’s fame, saying that his notoriety has reached Mexico, and states that there is a hit on his head.

The narcocorrido has a complicated history. They are songs often (but not always) paid for by a leader of a cartel, to condemn or laud a major figure in the drug trade or to send a message to someone. They can celebrate murders, big deals, or talk someone up. The performers lives can be endangered not only by whether their song is appreciated by the sponsor or the subject of the lyrics, they can also be under threat from an opposing group. Some of these performers write songs independently, without direct affiliation. Irrespective, it is a genre integral to the cultural reception and understanding of the drugs trade on both sides of the border. “Negro y Azul” at the opening of Breaking Bad is a good example of one of these, aesthetically plays with the low budget and often corny nature of the videos, and is performed by a hugely successful group. The series is directly using this popular form as an important allusion, thereby recognising its significance and interpolating Heisenberg/Walt into the meta-narrative the narcocorridos engage in as if he were real.

The music video also works as a neat shorthand way of telling us about the hit out on Heisenberg/Walt and to introduce us to Tortuga, Trejo’s character. He is glimpsed in the video as the lyrics declare that the cartel see Heisenberg/Walt as a threat and plan to eliminate him.  The shots of Tortuga are styled as if they were by security or surveillance cameras, he is seen mostly in shadow and the quick cuts ensure that shots of him are fleeting. He is implicitly slippery, bad, and hard to track.

The shots of Tortuga are styled as if they were by security or surveillance cameras, he is seen mostly in shadow and the quick cuts ensure that shots of him are fleeting. He is implicitly slippery, bad, and hard to track.

Later in the episode Tortuga is presented as having turned police informant. DEA officer and brother-in-law to Walt, Hank (Dean Norris), who has just been given a promotion to work alongside officers in El Paso, Texas, meets Tortuga for the first time in the hotel room he has been put by the police.  In this scene he belittles Hank

In this scene he belittles Hank

for not speaking Spanish and intimates that he will give them fuller information in the future. His attitude is arrogant.

for not speaking Spanish and intimates that he will give them fuller information in the future. His attitude is arrogant.

He is clothed in a hotel bathrobe with a cigar in his mouth and talks about the Television programmes he is keen to watch.

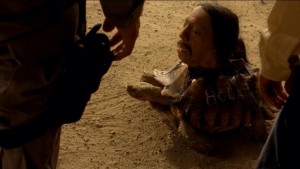

All of this suggests that he is happy to take but not to give. Put alongside his presence in the earlier music video sequence he is implicitly untrustworthy. At the end of the episode Hank comes upon Tortuga’s severed head when given a tip off by another informant.

This sequence suggests at the particular savagery of the Mexican cartels over anything that Hank has previously witnessed. Tortuga’s head is attached to a tortoise.It is first seen from afar through binoculars, then Hank and the other US and Mexican police agents approach it. Hank is evidently upset having already experienced trauma in an earlier episode when he kills Tuco, and runs to his car amidst laughter from his colleagues.

One asks, mockingly, “What’s the matter Schrader you act like you’ve never seen a human head on a tortoise before?”,

suggesting that they have seen much worse before and are inured to such violent deaths. Hank tries to cover up by saying that he is getting an evidence bag from the car. He is not believed. By this need to move away from the horror, he saves his life. On being touched by one of the other officers the head and tortoise explode. What follows is terrible moaning by the men who have survived and dark, unsettling noises on the soundtrack as the camera surveys the bloodshed. The later episode in which Tortuga appears shows the final events that lead up to his death. We are to read that Mexican brutality is more than Hank, as an experienced DEA can cope with, especially one based in New Mexico.

So, what of this representation? The police in El Paso, both Mexican and US, have become de-sensitized to this violence. El Paso is represented as more Mexican than New Mexico. This is particularly evidenced in the fact that the DEA are mostly bilingual and there is close cooperation between them and the Mexican police. Whereas, in New Mexico Hank gets away with casual racism and constantly demeaning his Mexican-American work partner because he is working in a predominantly Anglo office. Hank’s function in the narrative in this respect is to play out the tense relationship between the US and Mexico, which is a concept that merits further exploration elsewhere. While Trejo embodies the danger from the other side, threatening, untrustworthy, sleazy, and, even after death, capable of inflicting terrible injury.

Conclusion

In its representation of Mexicans, Breaking Bad rarely gets beyond the stereotypical. With the exception of Gus (as one of the few Latino to be fleshed out) and the drug lord in his crass over-blown mansion, all Mexicans are represented as dwelling deep in the countryside trapped by poverty in dusty hamlets, familiar from Hollywood cliché, but not familiar to the average Mexican experience. It is disappointing in a series which is otherwise nuanced, cleverly plotted, beautifully executed and intelligent, that the Mexicans are still the scapegoats. Whilst Schrader, Walt and other white characters are given multi-dimensional characterisation, Tortuga and many other Mexican characters are ascribed singular characteristics that conform to long-held stereotypical representations of Mexicans in US film and TV.