I am continuing my occasional posts about films starring María Félix with a short post on La estrella vacía [the empty star] (Emilio Gómez Muriel, 1958). The film is adapated from the eponymous 1950 novel by Luis Spota, a well-known chronicler of twentieth century Mexican urban life and, in the words of Sara Sefchovich a “fenómeno sociológico-literario” [sociological-literary phenomenon] (1979, 839), because of his attention to Mexican politics and society. A bestselling author whose work has been given little attention by scholars, Spota’s novel is indicative of his interest in exploring the “abuse by the powerful” of those less powerful in society (Pouwels 1994, 424-5). This is reflected in the adaptation.

María Félix stars as Olga Lang, a young woman of modest means who has moved from her village to Mexico City to become a film star. It soon becomes clear that she is ruthless in her pursuit of fame aligning herself with powerful men in order to fulfil her ambitions. Whilst this could be a simple story of a glamorous femme fatale, the plot is not concerned with Olga as a seductress. Instead, it is centred on everything she endures and the great sacrifices she makes in order to become rich and successful. The challenges are multiple and mostly inflicted by the powerful film industry men who have a say over her career and life. The hardships range in difficulty and include controversial issues that receive little attention in mainstream melodrama. These include being forced to undergo a botched abortion that leaves her unable to have children; missing her mother’s funeral; being subject to sexual harassment by the studio executives; and experiencing domestic violence and controlling behaviour by multiple partners. This exploration of the costs of fame has elements of what has been revealed through the MeToo movement campaigns. La estrella vacía foreshadows these revelations and suggests that such abuses have been a long-kept open secret. The studio bosses, Raúl Tovar (Ramón Gay) and Federico Guillén (Carlos López Moctezuma), are particularly prone to abusing their power. While the lowlier men, such as the novelist Luis (in what could be an allusion to Spota himself), Arvide (Ignacio López Tarso), Olga’s driver, Tomás (Wolf Rubinskis), and Olga’s father (José Luis Jiménez) are all more noble allies to Olga. Nonetheless, none of them shield her from the abuse.

Ambition has its challenges, but so too has a quest for independence. It is clear that life for a woman in the city is difficult, as evidenced in her friend, Teresa’s (Rita Macedo), struggle with her alcoholism, which is understood as a consequence of the challenges of city life rather than addiction. As Olga reflects after visiting Teresa in a psychiatric hospital, “hay que hacerse dura…muy dura”, implying that Teresa has that quality and, whilst Olga does, it has come at a cost.

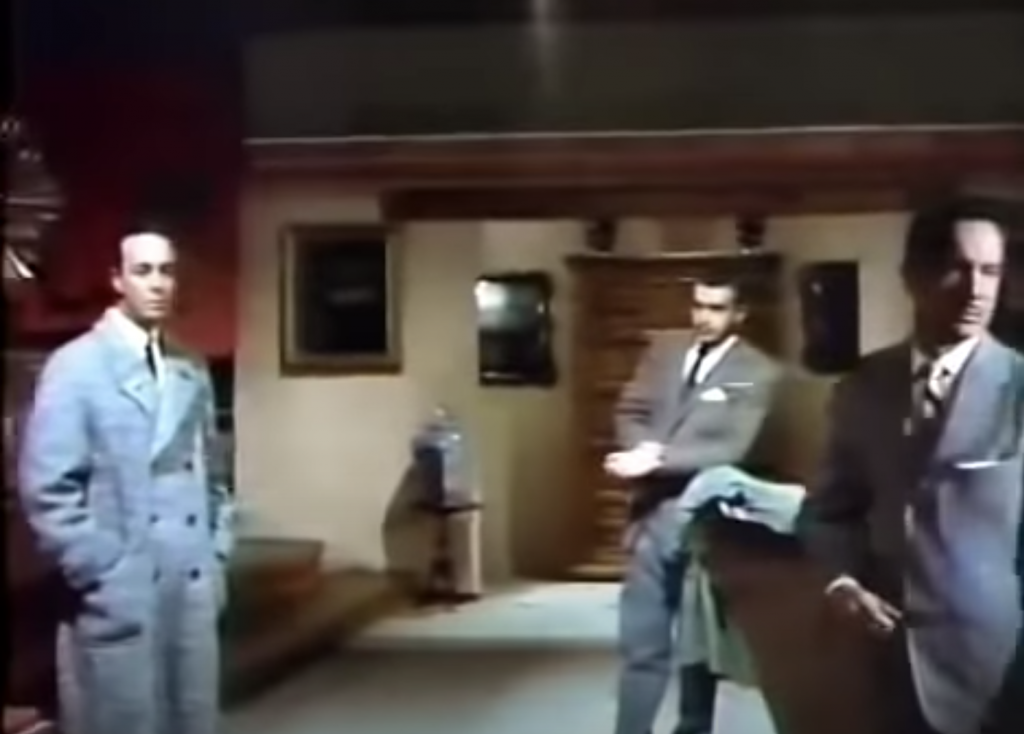

I’m not interested in a like for like comparison with the novel, but what is retained in the adaptation is structural experimentation, flashbacks are a framing device of both the novel and film (Pouwels 1994, 425). The film begins with Olga’s departure from the airport to Madrid which cuts to a news headline of her death in a plane crash. This then cuts to a modernist mansion and a panning shot of an open-plan room inside with men in different poses. Over the course of the narrative it becomes clear that these are all men who had a relationship with Olga as her parent, lover, friend, or employee. There are several flashbacks to this scene in the film to remind us of their significance and her death.

It would be easy to classify this film as a conservative lesson in punishment for female ambition. Whilst some of that is present in the film, that reading is simplistic and ignores the cruelty of the powerful that is being revealed to us over the course of the narrative and the significance of Félix’s star text that can be read as both sub-text and text in the film. As someone with insider knowledge of the film industry, Spota claimed that Olga was inspired by Félix, Dolores del Rio, and Gloria Marín (Taibo I 2004, 347). In part, this is Félix’s story. There is some moralising about women’s ambition, but this is not a cautionary tale about being ambitious, it is a warning about how power is abused by those who wield it.

Works Cited

Taibo I, Paco Ignacio. (2004), María Félix: 47 pasos por el cine. Mexico: Ediciones B.

Pouwels, Joel B. 1994. “Luis Spota Revisited: An Overview of His Narrative Art.” Revista Hispánica Moderna 47 (2): 421-435.

Sefchovich, Sara. 1979. “Luis Spota, La Costumbre Del Poder.” Revista Mexicana de Sociología 41 (3): 839. doi:10.2307/3540092.