The following was my introduction to Elena Poniatowska at City Hall.

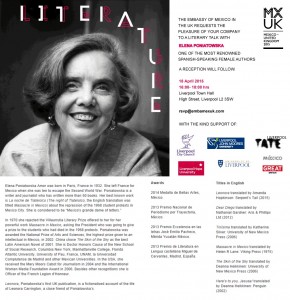

2015 will see a series of events related to Mexico and the United Kingdom. It is an honour to welcome Elena Poniatowska to Liverpool who has just been at the London Book Fair. Of course, she is here in Liverpool, now because of her fascinating fictionalized biography of the artist, Leonora Carrington, whose work is currently being exhibited in Tate Liverpool. I’m here to give an overview of Elena Poniatowska as author, journalist and activist from an academic perspective.

2015 will see a series of events related to Mexico and the United Kingdom. It is an honour to welcome Elena Poniatowska to Liverpool who has just been at the London Book Fair. Of course, she is here in Liverpool, now because of her fascinating fictionalized biography of the artist, Leonora Carrington, whose work is currently being exhibited in Tate Liverpool. I’m here to give an overview of Elena Poniatowska as author, journalist and activist from an academic perspective.

I first came to Elena Poniatowska’s work through research into the Mexican Revolution. Her book, Hasta no verte Jesús mío [translated as Here’s to You Jesusa], was first published in 1969 and is the story of a soldadera [or female soldier] in the Revolution. Based on interviews with a real-life individual, who refused to speak if Elena carried a recording device or notebook, it was filtered through memory, and was a radical departure from other novels of the Revolution, which had focused on the male prowess or failure on the battlefield or in politics. Instead it told the story of a woman born into poverty, forced through circumstances to take up arms and who continued to battle throughout her life and worked in a number of precarious jobs from child minding and cleaning to piecework in factories. It is a tale of survival told melding literary technique with fact in innovative ways that has marked Elena Poniatowska’s work over the course of her writing life.

Drawing from early techniques learnt while working alongside the US anthropologist, Óscar Sánchez, which were honed interviewing the rich and famous for Mexican newspapers, Elena Poniatowska is an adept interviewer. This is reflected in the multiple chronicles and testimonios she has published covering significant events and figures in Mexico. These include:

Tlatelolco Massacre [an account of the student movement and subsequent massacre in the days leading up to the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City];

Nothing, nobody: the voices of the earthquake [an account of the earthquake in Mexico City in 1985];

These are polyphonic stories of the subaltern. That is, they are books with many voices, which function as forms of witness to the events with multiple interviews with victims and their families.

Elena Poniatowska is not only interested in the disadvantaged. She has also written essays, interviews, and fictional narratives of artists, writers and activists. These are individuals who have challenged authority in different ways and have found creative means of expressing their dissent.

This diverse group includes essays on the feminist poet and essayist, Rosario Castellanos and the US photographer, Mariana Yampolksy, who became a Mexican citizen and spent her life documenting impoverished rural Mexicans, and a well-known interview with the elusive rebel spokesman for the Zapatistas in Chiapas, Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos.

She also writes essays about the important men of letters and art and takes on a new perspective, whether that is a new reading of the nobel-prize winning poet, Octavio Paz, or the imagined letters to the muralist Diego Rivera from his Russian artist wife Angelina Beloff, who he abandoned in Paris.

Never conventional, these are attentive to the view from the edges of history, the private lives of public figures as experience rather than spectacle, the mechanics of power, and those at odds with the mainstream. In this way, Elena Poniatowska is part of a strong Latin American tradition of the public intellectual, who the Uruguayan critic described in his book the “Lettered city”. He asserted that it is the responsibility of those who have the cultural and literary capital to recognize their privilege and engage in public debate. For him, through the creation of this critical space there is the potential to debate the discourses of power and this is something that is evident in Elena Poniatowska’s work.

Winner of many awards, writer of novels, short stories, essays and interviews, author of texts that have defied categorization [and have academics at odds over how to label them], she is a creative and intellectual force.

A precursor to the boom in women’s writing in Mexico of the 1980s and 1990s, Elena Poniatowska has mapped out her own particular trajectory as someone who has drawn attention to those at the margins and those the official histories have forgotten or would rather forget.

Never afraid of speaking truth to power and of advocating for the marginalized, Elena Poniatowska remains a vital voice in Mexican literary, social and political life.