This post is about the American Dirt Controversy. It is as much archive and tracking an online news piece in my corner of the Twitterverse as it is about giving an account.

In a previous post I wrote about the opening salvo that has grown into a fascinating conversation about who the publishing industry supports, who it deploys to market a book, who are the key tastemakers in the industry, and, most importantly, why certain truths really matter.

To recap, the writer, activist and teacher, Myriam Gurba was commissioned to a review for Ms that they decided not to publish on the basis that it was too negative. On the 12th of December 2019 Gurba wrote about her review and her reflection on the magazine’s refusal to publish it on the academic blog site Tropics of Meta, “Pendeja, You Ain’t Steinbeck: My Bronca with Fake-Ass Social Justice Literature“. At first this got little attention. In the lead up to the publication date of the novel on the 21st of January 2020 and its endorsement by Oprah for her book club, Gurba’s post went viral and the Twitter discussion really took off. This was further fuelled by a number of seriously mis-guided publicity moves including, barbed wire decor for the launch party that led to accusations of “using migrants as props” and of bad taste when the author re-tweeted (later deleted) a fan’s nails painted with the barbed wire of the book’s cover.* Some of these posts, including those linked already from Mic and Vice, as well as this Buzzfeed article, give an account of the initial controversies. These look at the cover, the content, the industry, the author (to use and extend Buzzfeed’s helpful subheads), as well as the money, and more importantly, who tells whose story.

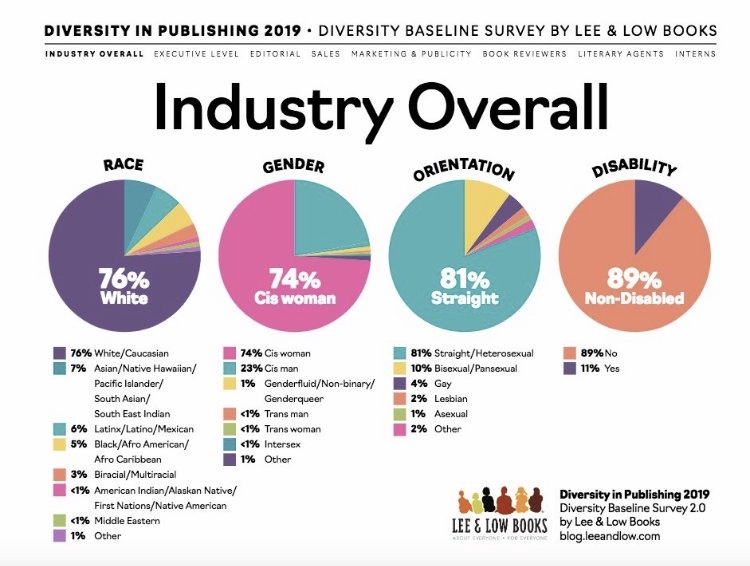

There have been a number of pieces on whether non-Mexicans can write stories about Mexico and Mexicans. Some of this has been an exasperation with white privilege, although not generally expressed in this way (given how frequently this phrase is wilfully misunderstood). In this case it means that if you are white the struggle to publish may be real, but the odds are stacked in your favour especially when contrasted with anybody else. These stats give a sense of the problem:

Other takes have been about class and how New York centred the publishing industry still is, which means that it seems to struggle to include voices outside of that elite. Daniel A. Olivas makes the case in The Guardian when he says,

“Yes, we are angry. But we will not be silenced. We are Latinx writers – with the support of our allies – who have been fighting too long to stop now. Radical change is needed in the publishing industry, not simply with respect to Latinx writers, but all marginalized writers who have important stories to tell based on their own lives and experiences.”

Who gets to tell stories is important and this is not a new fight nor unique to Chicanx or Latinx communities. For example, in the UK, Kit de Waal (amongst others) has called for more inclusion of working class voices. She makes a powerful case for this here. The challenge within this debate has been that vital voices who have been speaking about this for years, are having their voices heard and then silenced again as if there is an economics of scarcity in all of this which presumes that there isn’t space for a range of voices. De Waal finishes her article on that point, championing the voices of those from a wealthy background who have enriched culture and making it clear that,

“[t]his isn’t a plea to take them off the shelf. It isn’t a case of us or them; it’s a case of us and them. Shove all those other books up a bit and make room on the shelf for stories from all of the communities that make up the working class. We do literature and ourselves a disservice if we don’t.”

Olivas makes a similar point in his article when he says,

“it’s not that we think only Latinx writers should write Latinx-themed books. No, this is not about censorship. A talented writer who does the hard work can create convincing, powerful works of literature about other cultures.”

Similarly, Ignacio M. Sánchez Prado, in a Twitter thread turned Washington Post article, challenges the premise that Mexicans are an ethnicity and that only Mexicans can write about Mexicans. To that end, he gives a list of books about Mexico by Mexicans and non-Mexicans as alternatives to American Dirt. Many of these lists have been put together as a direct response to Cummins assertion that she is speaking for a “faceless brown mass” of Mexican humanity as if there aren’t Mexicans and Latinx writers.

Elsewhere, other lists of alternative books have emerged. There have been a number of repeated names, such as Luis Alberto Urea**, Yuri Herrera, and Valeria Luiselli, as well as mention of books by other notable and, perhaps, less well known authors. Here are some examples, The Texas Observer, Vox and The Guardian. As Reyna Grande asserts in The New York Times, the upside of the publication of the novel has been that “American Dirt has us talking”.

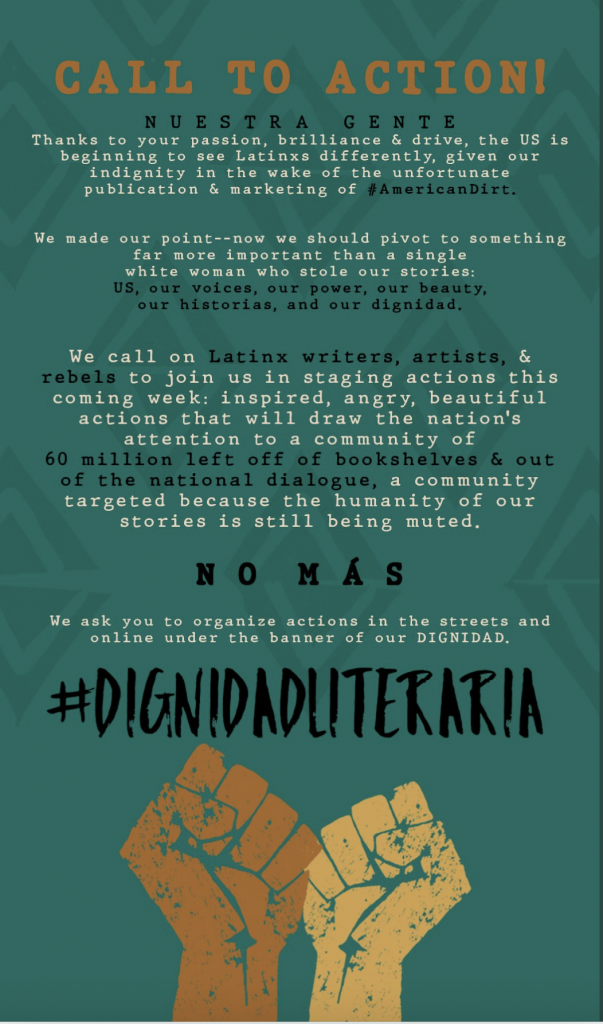

Thus far, the novel has led to two separate hashtags. The “writing my Latino novel” meme that parodies the novel’s missteps in code-switching and the clumsy ways it deploys Mexican stereotypes. The first meme is deliberately humorous and satirical, whilst the second, #DignidadLiteraria, has emerged from an activist demand to be heard and read.

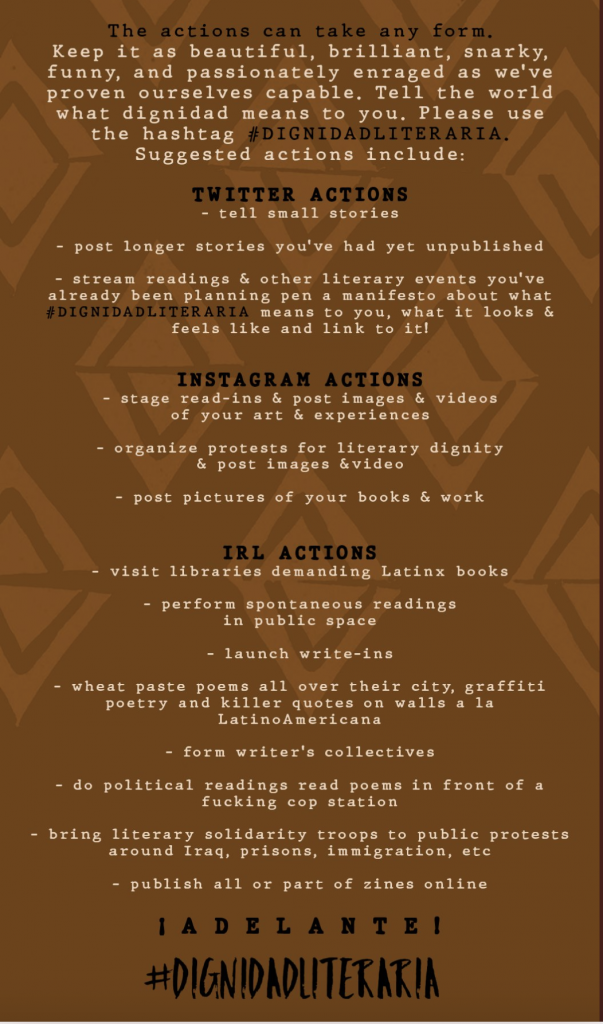

The related ere call to action, as shared by author and journalist Roberto Lovato (@robvato), reveals the clear intentions of the hashtag:

As a result of this activism and controversy, readings have been cancelled and celebrities have withdrawn their endorsements, whilst authors, such as Sandra Cisneros, have been criticised for continuing to support it.*** More worryingly, Gurba and others have received threats. An open letter signed by 137 writers has been published on LitHub asking Oprah to withdraw her endorsement asserting that,

“in a time of widespread misinformation, fearmongering, and white-supremacist propaganda related to immigration and to our border, in a time when adults and children are dying in US immigration cages, we believe that a novel blundering so badly in its depiction of marginalized, oppressed people should not be lifted up.”

We need to ask the same of the BBC. American Dirt is still slated to be Book of the Week in April 2020****. They should reconsider their endorsement.

From my place online, the consequences of this controversy have led to an exciting conversation around literature and its significance, fascinating reflections on the importance of truth in storytelling, and a brilliant sharing of names and voices that may otherwise have gone unnoticed. For Cummins and her publisher the consequences are less clear. The book is number one on Amazon’s bestseller list, so something is working for them. We will have to wait and see whether there are any long term changes in the publishing industry.

Some notes

*If you want more on barbed wire’s iconography, go to María Herrera-Sobek’s chapter, here.

**Suggestions have been made that some of the novel may have been “cribbed”.

***For those who want to listen to Gurba, Urea, Cisneros, and Cummins speak about this controversy NPR’s Latino USA have put together a great program.

****Addendum: it was aired from the 6th-16th of April 2020.