Over the last 24 hours multiple writers and newspapers have marked the centenary of María Félix’s birth on the 8th of April 1914. In curious symmetry she also died on the 8th of April in 2002 at the age of 88. She is an unfamiliar figure in the English-speaking world. She never acted in an English-language film, and although some of the films she starred in were in the official selection at Cannes few reached the English-language marketplace. However, in Mexico, more widely Latin America, and areas of Europe, such as Spain, Italy and France, she did make a significant mark.

She appeared in 47 films over the course of her career and became known as La Doña after her breakthrough role as the eponymous character Doña Bárbara (Fernando de Fuentes and Miguel M. Delgado, 1943). A sampling of her performances can be found here and here. What is notable about these samplings is that they highlight the ‘quality’ films, that is the ones recognised as having value because of the credentials and reputations of the directors (Mexican and international, for example, (Emilio “Indio” Fernández for Enamorada (1946) and Río escondido (1948), Los ambiciosos (Luis Buñuel 1959), Sonatas (Juan Antonio Bardem, 1959) or French Can Can (Jean Renoir, 1954)), or for the awards she was granted for them. They ignore the more troubling populist ones, often of colour, which are still often looked over by academics. In these films she plays a significant role in the bellicose period of the Mexican Revolution (1910-20) and is a transgressive woman. She cross-dresses, plays the prostitute, drinks, carouses and generally disrupts the idea of what a good woman is. While she often (although not universally) played the femme fatale in many of the films mentioned in the articles, which allows for transgressive behaviour, these other films set during the Revolution upset the clear narrative of respectability and comfortable commemoration.

She appeared in 47 films over the course of her career and became known as La Doña after her breakthrough role as the eponymous character Doña Bárbara (Fernando de Fuentes and Miguel M. Delgado, 1943). A sampling of her performances can be found here and here. What is notable about these samplings is that they highlight the ‘quality’ films, that is the ones recognised as having value because of the credentials and reputations of the directors (Mexican and international, for example, (Emilio “Indio” Fernández for Enamorada (1946) and Río escondido (1948), Los ambiciosos (Luis Buñuel 1959), Sonatas (Juan Antonio Bardem, 1959) or French Can Can (Jean Renoir, 1954)), or for the awards she was granted for them. They ignore the more troubling populist ones, often of colour, which are still often looked over by academics. In these films she plays a significant role in the bellicose period of the Mexican Revolution (1910-20) and is a transgressive woman. She cross-dresses, plays the prostitute, drinks, carouses and generally disrupts the idea of what a good woman is. While she often (although not universally) played the femme fatale in many of the films mentioned in the articles, which allows for transgressive behaviour, these other films set during the Revolution upset the clear narrative of respectability and comfortable commemoration.

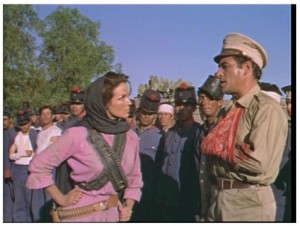

Her posture, assertive screen presence and the transgressive nature of her performances can be sampled through these screen grabs from such films.

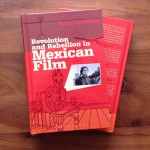

These films may be overlooked because “Cucuracha” or cockroach became a label for big budget failures for a time in Mexican cinema. However, I argue that these films have much that is worthy of consideration. This is something I discuss in detail in one of the chapters of my recent book. It is for that reason Félix even gets a special place on the cover.

The multiple vids created by YouTubers have also navigated this line between hagiography and a celebration of a more complex and contradictory star text, which I have also discussed elsewhere. By way of example, here is one that celebrates the glamorous Félix. It is accompanied by a song, “María la bonita”, written for Félix by one of her husbands, Agustín Lara.

This other one goes further in challenging the standard view of Félix among journalists and academics and provides a useful and entertaining overview of her entire ouevre and includes the popular, populist or critically acclaimed alongside the generally disregarded and ignored.

In an introduction to a book of photographs taken by her son, the Nobel prize-winning poet and essayist Octavio Paz (whose centenary is also being commemorated this year) said of Félix, “María Félix nació dos veces: sus padres la engendraron y ella, después, se inventó a sí misma” [María Félix was born twice: her parents gave birth to her and she, later, invented herself]. It seems that those writing about her also join in the game and have chosen to re-invent her several times over.